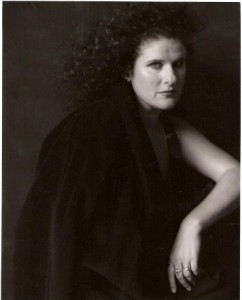

Judith Mok

Poetry is a pink apron.

Recently, I remembered wearing a pink apron when I was nine years old and went to the girl’s school the: Ecole Frederic Mistral in Menton on the Cote d’Azur in France.

The apron, our uniform in class, was something I had never worn in Holland, the country where I was born.

Nature orchestrated wild background music to the first lines of poetry I heard in that country. My father, his friends, my mother, their hands resting on the old-fashioned damask tablecloth after dinner would quote Heine, Goethe, Baudelaire, to emphasize a feeling or an idea we discussed before I went to bed.

There I listened to the wind’s whistle in the helm grass, the North sea breaking my slumber rhythmically, the German, Russian, French words in my head. Those words were like the first blocks to build up my tower of poetry :I was climbing the invisible stairs to my own library of poems.

The ground rule that poetry was the most important tool in life to survive, I learned as soon as my ears were conscious of language.

The ground rule that poetry was the most important tool in life to survive, I learned as soon as my ears were conscious of language. A lot of languages were strewn around me, I was picking up the sounds like confetti. And then there was music, heard on the radio and in the Concertgebouw the main concert hall in Amsterdam.

Soon, I stood and sang my first songs, dressing up the words with simple melodies. An army of composers marched into my early years, Brahms, Bach, Mozart. Or I learned about the bitter songs of Edith Piaf heard when I was playing at parties, parties for young and old and death, always present, dancing along, or so it seemed. A war had come and gone through my parents lives. I held hands with ghosts, as I held the books of those who were long dead and thought of them as my friends, alive and well.

By the time I was eight years old I was given to live in the French language. That’s where I stepped on the stage of poetry in my pink apron. The apron seemed to protect me from the staring eyes of my mean class maidens.

I recited my first entire poem in French, a poem by Rimbaud that set my tongue on fire. But nobody noticed, because of the apron I wore, I could pretend I was just giving my recitation and hide the surge of excitement that I felt for these words. I wrote Rimbaud, Mistral, La Fontaine poems in a yellow notebook, with a pen and ink, in curly handwriting. The serpent like tails of the L and M are still haunting me. My own first lines came from the graves of Russian princes: after school I climbed up to the cemetery, sat on the cool graves overlooking the Mediterranean, sea and sky creating a blue cradle for my young dreams.

The dead were those who had come from Russia, England, come from other countries like me, to live and die there. Precious stones fell from their tombstones and I started to compose a poem while picking up this treasure.: my first poems were weighed down with shards of gold and lapis lazuli. I held death close, I held solitude closer, I wrote some words as a child. I have not grown older since.

My roots are like bad plants, feeding of the earth of others, pure linguists, people expressing some light, some love with great strength in the poetry of their country. And I catch them, whispering words like” y los suenos” to myself, tasting a desperate love in the Spanish madrugada ,and I lose them on an Irish beach, reaching out to tear a veil, the one between English and Irish poetry. Or I stand, poor, on a mountain of music and words learned and forgotten, structures studied and used. There were tales that I thought taught me how to ride along on this monstrous animal of my own creation, my demon, and how to struggle for a description of it in my words. In the Dutch language words blossomed, I wrote books, then Dutch dried out, leaving me little more then the memory of a flat landscape without any horizon. The French language continued to sing in my head. I repeat Verlaine in la bonne chanson to myself. A triumphant ” Je vous aime”. Who will I address this to? I still don’t know. Then the English language moved in with me, made me sweat in the night, made me write.

Listen to The Parlour Review interview with Judith Mok

EXTERNAL LINKS

Leave a Reply